August 8, 2024

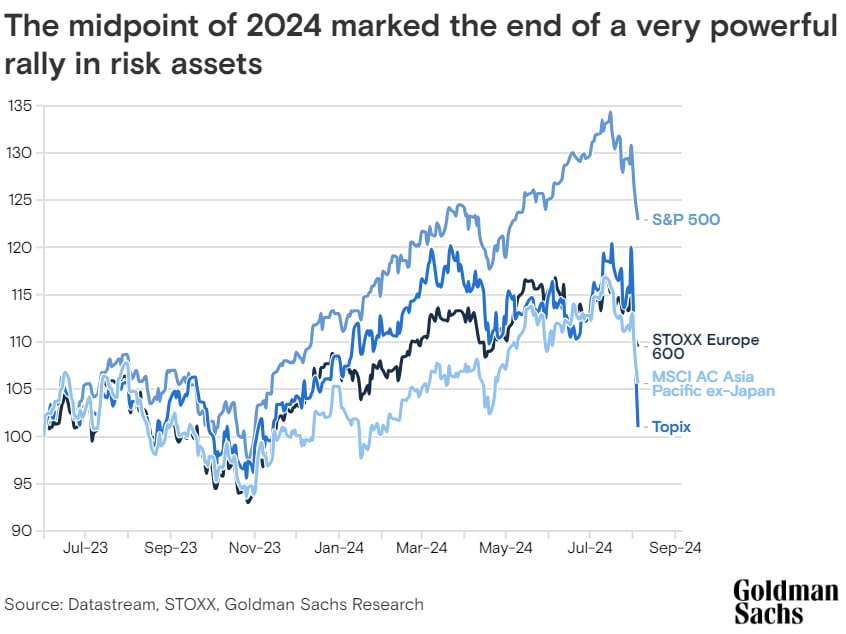

Stock markets from New York to Paris to Beijing are showing signs of correcting. While the reasons differ from one region to another, a moderate downturn in equities is widespread, and volatility is likely to persist over the coming months, according to Peter Oppenheimer, chief global equity strategist and head of macro research in Europe for Goldman Sachs Research.

In many cases, stocks are priced for a best-case scenario and so investor patience for a miss is low, says Oppenheimer. He finds that, during this earnings season, companies that are not meeting expectations are being heavily punished.

From their peak in July, the US’s S&P 500 Index is down 4%, the STOXX Europe 600 declined 5%, and China’s CSI 300 dropped 6% (as of Aug. 7). In some markets, recent declines follow a period of strong returns; the S&P 500 is up 10% year-to-date.

Oppenheimer predicts relatively flat stock index returns in most markets for the remainder of the year, and also potentially for the next 12 months. “That’s one of the reasons we have talked about focusing on increasing diversification to improve risk-adjusted returns — trying to spread out the risk investors are taking in terms of geography, sector, and style of investing,” he says. “We’ve also talked about hedging strategies to protect on the downside.”

Why the US stock market is in a correction

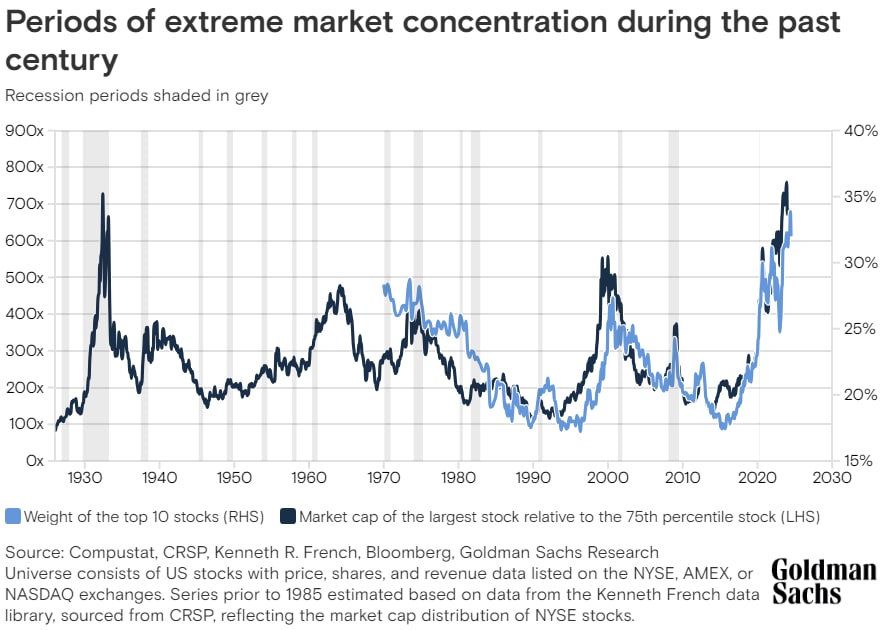

In the US, stocks have been buffeted as investors question the sustainability of the AI boom, which has disproportionately benefited a handful of mega-cap tech stocks.

“Valuations got a bit frothy,” Oppenheimer says. “Hopes and excitement about IT, and AI in particular, have started to fade just a bit, so a correction has seemed likely, and we are seeing the start of that. It is likely that volatility and the correction have further to go. However, a prolonged bear market is not likely”

Some smaller companies have started to outperform. As inflation slows, Goldman Sachs Research expects the Federal Reserve to start cutting interest rates and lower borrowing costs. Small cap companies are more sensitive to interest rate moves, because they have more debt and weaker balance sheets in aggregate. That said, small caps are also more cyclical, so Oppenheimer remains cautious in the event that the economy slows too quickly.

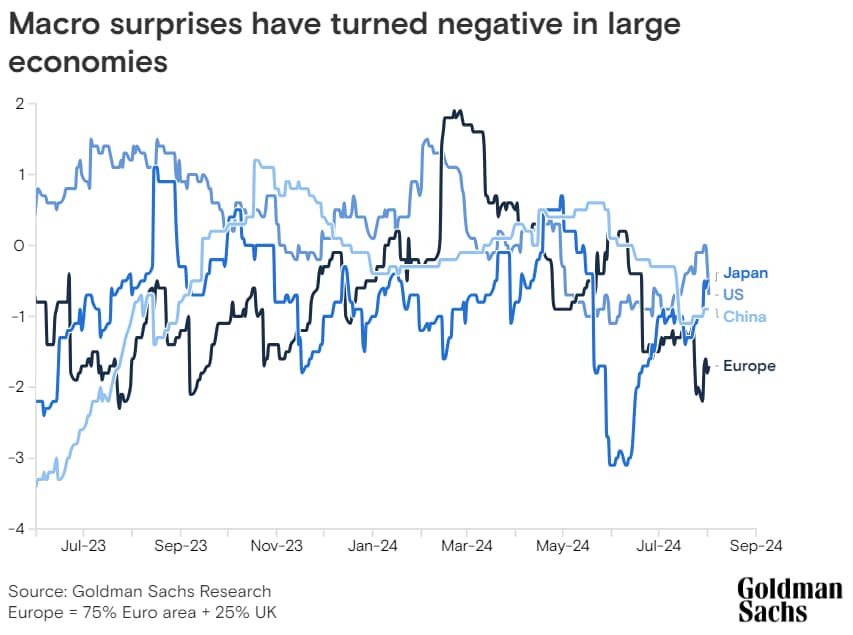

How the stock market correction is playing out in Europe and China

The outlook for Europe’s economy has dimmed amid ongoing weakness in the manufacturing sector and the threat of tariffs from the US in the event of another Trump administration.

“In Europe, it’s less about a correction in large cap tech,” Oppenheimer says. “The exposure to large cap tech is much smaller. What you’ve seen in Europe is weaker economic activity driving earnings downgrades for the market more broadly, and you’ve seen growing concerns about the political sphere.” For example, “the inconclusive results of the French election have left a vacuum, and we’re not likely to see progression toward further reforms,” he adds.

This year, an eclectic mix of companies has outperformed in Europe. Some defensive companies, such as healthcare stocks, have gained, along with cyclicals such as banks. While lenders are often under pressure when the economy slows, Oppenheimer points out that European corporate and household balance sheets are relatively strong, which makes a wave of credit losses less likely. At the same time, Europe’s bank stocks have retreated so much over the past decade that the risks to valuations are limited.

And while the European Central Bank is cutting rates, Oppenheimer says there’s less room to lower them relative to the US or UK, because rates peaked at a lower level. “Lower interest rates will help the economy in Europe, but I think the concern on the economic side is much greater than in the US,” he says.

In China, economic data has been subdued for some time amid a protracted slump in the housing market and a drop in consumer confidence. That is rippling through the domestic economy and also impacting companies in Europe that benefit from exports to the world’s second-largest economy.

“The Chinese economy continues to weaken,” Oppenheimer says. “That’s leading to downgrades to growth expectations for companies directly exposed to China. Germany, in particular, has large manufacturing exposure and is sensitive to demand from China. Demand for luxury goods from China is also slowing.”

Will stock markets fall into a bear market?

“We’re not likely to see a bear market,” Oppenheimer says. “There’s room to cut rates if growth really does decelerate. A recession is pretty unlikely, and generally it’s recessions that drive bear markets, as that’s when profits start to fall.”

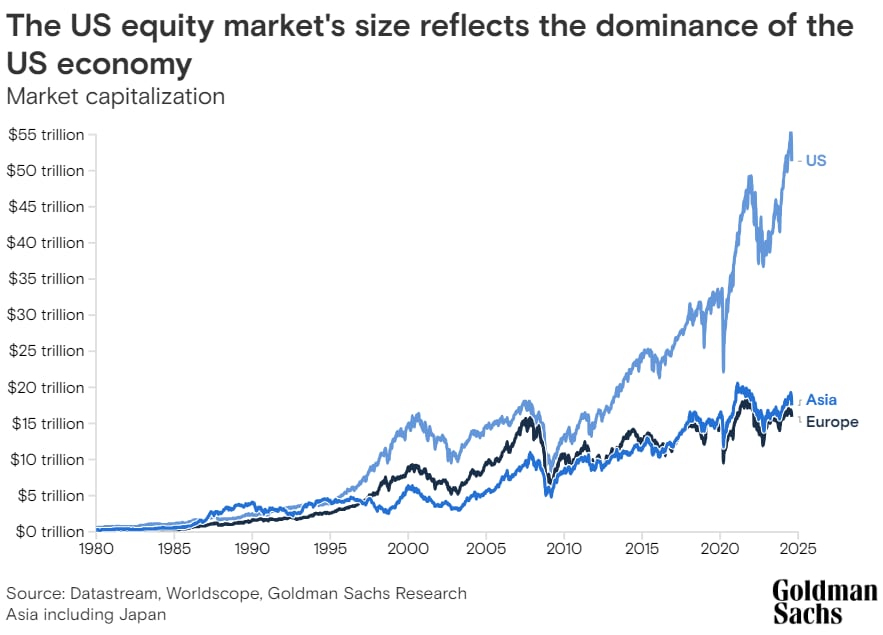

Even so, there are several key trends that Oppenheimer says investors should be mindful of. For one thing, the size of the US stock market has diverged immensely from other equity markets since the financial crisis in 2008. “The question, in some sense, is why it’s happened to such an extreme degree — it’s a bit unprecedented,” he says.

While the US has had the largest stock market and the biggest economy for a long time, the gap with other markets has widened since 2008 far more than in the past. “To some degree, that’s because the US had a more successful recovery after the financial crisis than Europe or Asia,” he says.

The US market cap has also grown considerably relative to GDP, whereas that ratio is roughly unchanged in the rest of the world.

Oppenheimer says that isn’t necessarily a sign of irrational exuberance. US companies have seen much more profit growth than their counterparts in the rest of the world, and that difference helps explain the scale of the market capitalization. In addition, tech companies have had the strongest growth in profits since the financial crisis, and tech is a much larger component of the US market.

But that has also resulted in a US market that has substantially higher valuations than markets in other geographies around the globe. “It implies that the advantage in the US will continue in the future, but that isn’t necessarily clear,” Oppenheimer says. “This isn’t a reason to say the US is likely to structurally underperform. But there may be more reasons to be more diversified geographically as the valuation gaps become more extreme.”

Profit margins around the world may be at risk

A potential decline in profit margins is another long-term trend that investors should watch, Oppenheimer says.

“It’s important to recognize that profit margins in the US, Europe and elsewhere have been structurally rising for many years,” he says. “For a long time, that reflected important tailwinds. Globalization helped boost profit margins through lower labor costs and so on. There’s been a period of declining tax rates.”

Now there are signs that corporate profit margins may have peaked, and input prices are rising. Labor and energy costs may climb, and increases in interest charges and taxes are likely over time, Oppenheimer says.

“There is a concern that, over the medium term, if profit margins are flat or come down, then earnings growth will weaken,” he says. That could filter through to stock prices, which reflect future growth and the margins that companies can achieve.

“Really focusing on valuation is important, because we have to acknowledge that there are parts of the market with high valuations and potentially weak margins,” Oppenheimer says. “That’s something we want to reflect through more diversification, more hedging.”

This article is being provided for educational purposes only. The information contained in this article does not constitute a recommendation from any Goldman Sachs entity to the recipient, and Goldman Sachs is not providing any financial, economic, legal, investment, accounting, or tax advice through this article or to its recipient. Neither Goldman Sachs nor any of its affiliates makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the statements or any information contained in this article and any liability therefore (including in respect of direct, indirect, or consequential loss or damage) is expressly disclaimed.